Climate change and human health

Brown’s IDeA Symposium on the Health Effects of Environmental Change reveals climate change issues have an unrelenting impact on our health and broad implications for the medical community.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Climate change poses current and increasing hazards to human health. As the planet warms, health risks are increasing, threatening not only individuals but also public health and the healthcare system.

Risk factors are felt across the globe. Air pollution and wildfire smoke worsen asthma and allergies and contribute to heart and lung diseases. Extreme heat can cause heart failure, heat-related illnesses, and even death. Drought leads to dust storms and Valley Fever, while flooding can create indoor mold and fungi. Changes in disease patterns increase the risk of Lyme disease, West Nile Virus, malaria, and encephalitis. Additionally, warmer waters lead to harmful algal blooms and more waterborne diseases.

Understandably, people are feeling climate change anxiety. Stress, depression, feelings of loss, and post-traumatic stress disorder are linked to rising temperatures, increasing greenhouse gas levels, rising sea levels, and more frequent extreme weather events.

The need to address these health concerns drove the theme of the 17th annual Rhode Island Emerging Areas of Science IDeA Symposium, “Health Effects of Environmental Change,” held on October 24th, 2024, at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

“It's obvious to all of us that our environment is changing in many different ways, and not the least of which is climate change,” said Sharon Rounds MD, principal investigator for Advance Rhode Island Clinical Translational Research (Advance RI-CTR), associate dean for translational science at the Warren Alpert Medical School, and professor of medicine, pathology, and laboratory medicine. “But in addition to climate change, there have also been changes in air and water quality. Microplastics are a ubiquitous problem, especially here in the Ocean State.”

The health costs of plastic

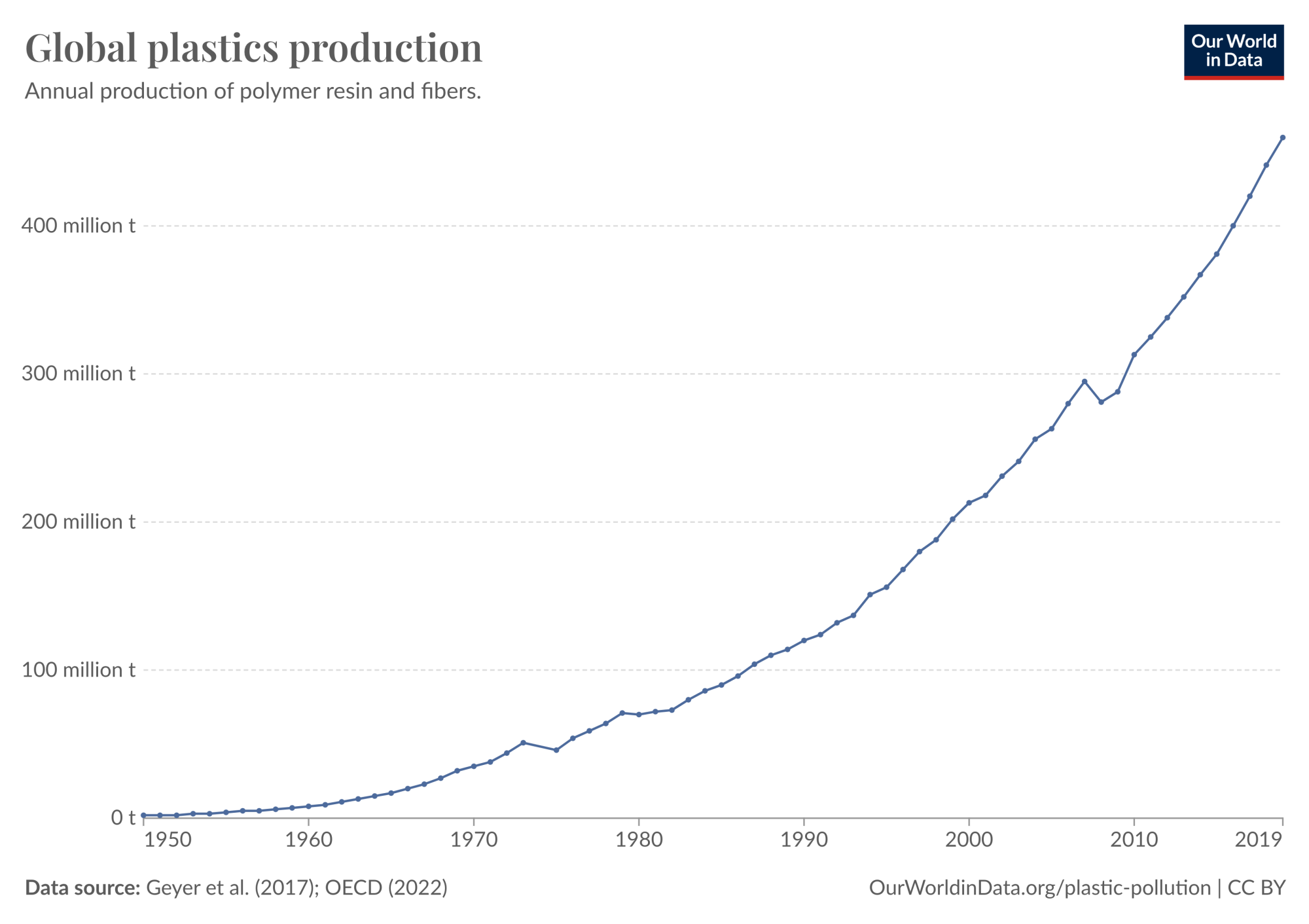

The world's production of plastic has skyrocketed from two million tons in 1950 to more than 450 million tons annually, of which 400 million tons each year is plastic waste. The durability that makes plastics desirable also means they never fully break down. Instead, they degrade into ever smaller pieces. Plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters are microplastics, considered dangerous because they contain toxins that can be inhaled, absorbed, and accumulated in organs.

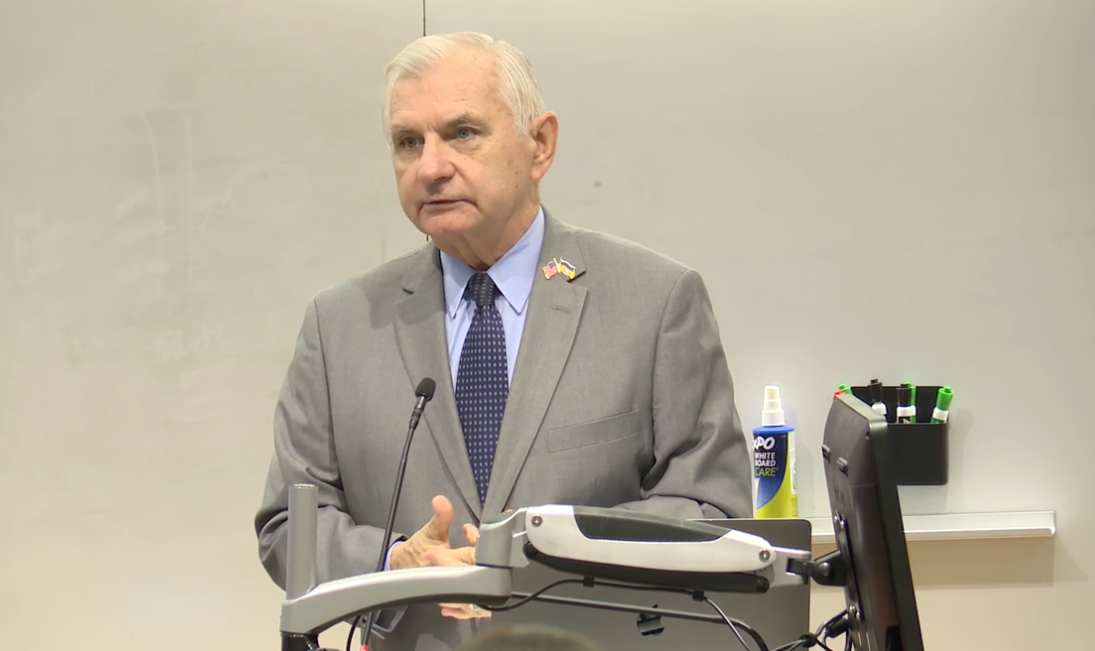

“Last year, the University of Rhode Island published a study that estimated that the top two inches of Narragansett Bay now contain more than 1000 tons of microplastics, tiny particles of broken down plastics,” said Rhode Island State Senator Jack Reed in his opening remarks. “It's built up over just the last 10 or 20 years. And these microplastics have made their way into everything including the food chain. They've been detected in all different types of species of marine animals, from plankton to commercial seafood and whales. They've also now been discovered in human beings.”

Rhode Island State Senator Sheldon Whitehouse amplified this concern in recorded video remarks from Washington, D.C. “Plastic pollution is now throughout the oceans from the bottom of the Mariana Trench to the farthest away islands and shores, even in our beloved Narragansett Bay,” he said. “It's now estimated that there are 16 trillion pieces of microplastic, adding up to maybe a thousand tons of plastic. And we have a lot of work to do to figure out what that plastic means when we ingest it, and it gets into our digestive system, brain, and organs.”

To understand the impact of plastic on the coastal system of Rhode Island, keynote speaker J.P. Walsh, professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography, collected sea floor and shoreline samples of sediment, measuring the surface concentration of microplastics for the URI study referenced by both senators. He then took cores from marshes and estuaries to examine the sedimentary record. “The cores all show this trend of very high concentrations of microplastics at the surface decreasing to near zero as we go back to sediments that are dated around 1950,” said Walsh.

Throughout the study, sediment samples showed microplastics of every shape, size, and color. “One of the problems of our plastic issue is that we can't singularly deal with the problem in one industry. It's coming from so many different sources,” said Walsh.

What are the consequences of these plastics in the marine environment?

“One of the things we're trying to understand is at what concentrations do we see direct species impacts of plastics? And the research has shown that for a small percentage of species, there's the threshold of about 540 microplastics per kilogram where we are seeing some measurable impacts on their physiology and function,” said Walsh. “This is a concern because when we compare this to our initial data, our samples from the surface of Narragansett Bay are above that 540 threshold.”

The less plastic we use, the better off we are

“Plastic is a big problem, and it's only increasing now. I don't think a bottle bill or a plastic bag ban will be the solution. We need to be doing more,” said Walsh.

“First, as individuals, we should think less about recycling and more about how we reuse, refuse, reduce, and repair items. Ultimately, our systems need to be thinking about a circular use of the goods that we make. How do we not have a single use of anything but rather, once it ends its single use, it ends up into some other useful product.”

Senator Reed recommends more research studies and project proposals. “We are looking at the cumulative effects of 150 years of human activity and it has both benefits and costs, and I think we're beginning to recognize the cost dramatically,” said Senator Reed. “We have to increase our knowledge in this area. That is the best way to deal with these emerging problems.”

Reduce emissions to reduce medications

In addition to studying the health effects of microplastics in our shifting coastal and marine environments, it is crucial to understand the health effects of our changing and warming planetary climate.

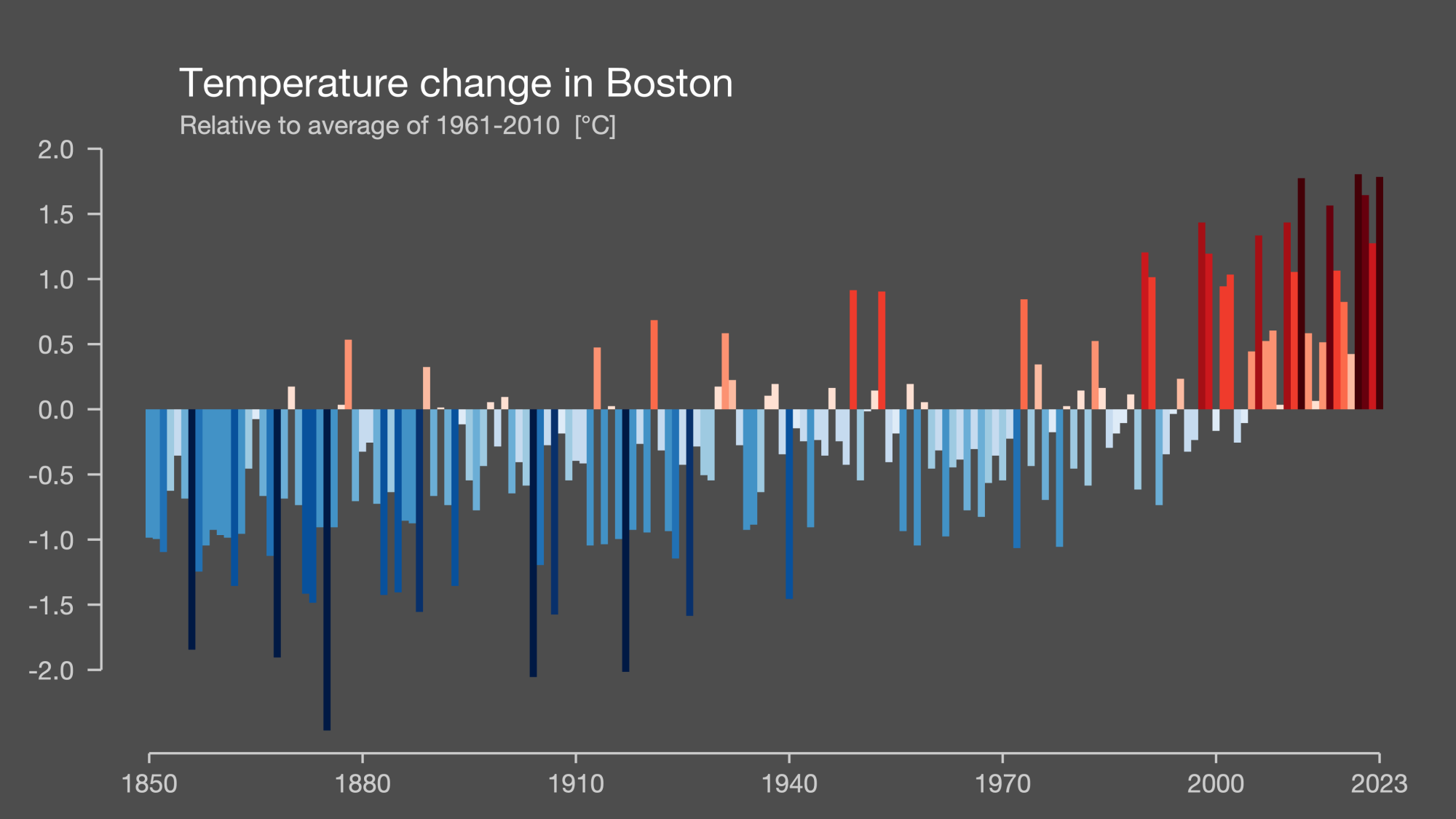

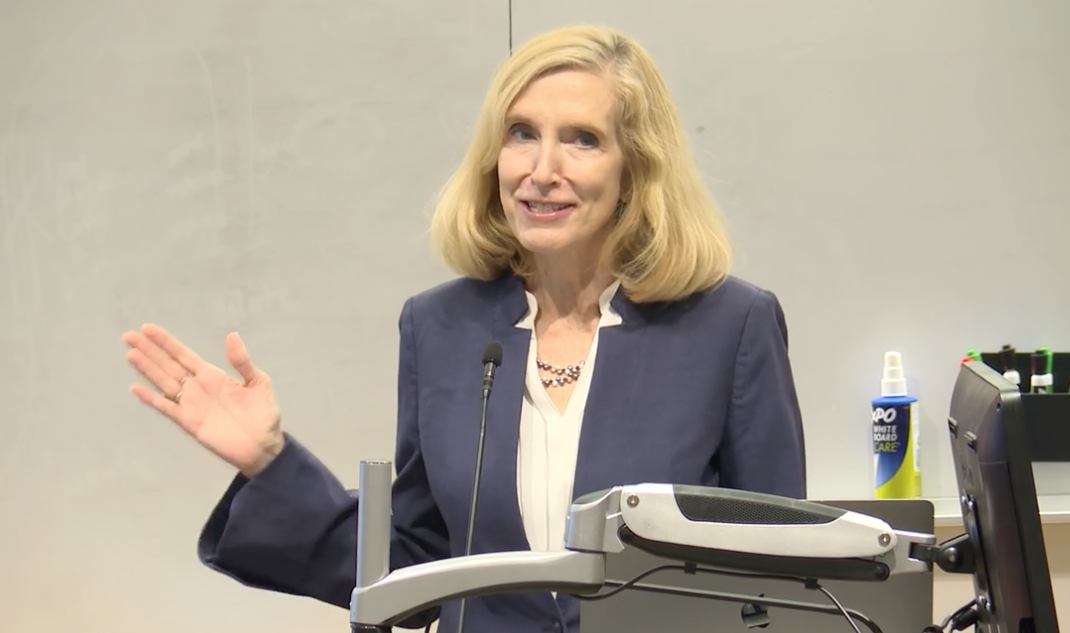

“When we look at what's going on across the centuries and millions of years and billions of years of our planet, we are truly in the Anthropocene era. We are using fossil fuels beyond reach. And because of that, we have increased greenhouse gases,” said keynote speaker Kari Nadeau MD, professor of climate and population studies and chair of the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “We also have methane and other fumigants in the atmosphere that are increasing greenhouse gases and staying longer than we thought in the atmosphere. And that's leading to increased temperatures.”

Greenhouse gases (GHG) include carbon dioxide (CO2), accounting for 65% of GHG emissions, nitrous oxide, chlorofluorocarbons, and methane. The last time CO2 levels were this high, Nadeau noted, dinosaurs walked the earth.

Increased temperatures affect human health. Heat waves impact mental health, drought and heat impact kidneys, mold and plant changes affect allergies, warming and flooding lead to infections, and air pollution causes cardiovascular disease.

“For any given change associated with climate change in terms of flooding, rising temperatures, extreme weather conditions, increasing greenhouse gases, and rising sea levels, any one person can be suffering from more than one of these health issues at any one time.

“The other problem is that any child now born on our planet will suffer through at least one extreme weather condition associated with climate change. So there will be a compounding effect of the longitudinal nature of climate change exposure and health issues with that given individual on this planet. Not only children but also older individuals as well,” said Nadeau.

At-risk groups targeted by climate change include older adults, those with comorbid conditions, underserved communities located near highways or toxic waste dumps that are already inequitably exposed, and children, because of chronic exposures and their increased metabolism.

“Air pollution affects two billion children on our planet,” said Nadeau. “Eighty percent of the world's children live at WHO standards above the threshold for pollution. Reduce emissions, and you reduce medications, and this is just for children.

“Across the globe, all humans are being affected by climate change. This has been a wake-up call both directly and indirectly. Nutrition is being affected, plants are being affected, animals are being affected, and vulnerable populations need to be looked at to make sure no one is left behind.”

Planetary health and human health are interconnected

“We are a species that needs to live in a coordinate fashion with this planet, and our health is inextricably connected to the health of our planet,” said Nadeau. “We have these concepts of planetary health, one health, and I want to make sure that we drive that today as part of our solutions. We need to think about biodiversity, and we need to think about how to rewild the planet to be able to improve planetary health as well as our own health.”

Nadeau recommends nature-based solutions and behavioral changes to improve planetary and human health.

Nature-based solutions to reduce allergens, temperature, and CO2 include greenhouse gas reduction, flood and erosion control, coastal defense, prescribed burns as forest management, cooling and shading, food and water security, and greening areas and buildings to sequester carbon.

“I hope if you take home one message, it's this: if you plant trees in a city and you increase the tree canopy by 30%, you reduce your temperatures in the inner city by 1.3°C, preventing one-third of premature deaths attributable to urban heat islands in summer. A 30% increased tree canopy yields a 30% reduction in premature deaths,” said Nadeau. “People saw the benefits within days of making sure the canopy was increased in cities.

“Many of these solutions need to be hyper-local and community-driven. And we need to have community engagement. So when we talk to communities, we ask them what is the most pressing issue? We don't necessarily use the word climate change. We use the word heat stress or flooding or algal bloom.”

Behavioral changes include transitioning to healthy sustainable practices, removing fossil fuel subsidies, increasing access to healthy transport options, strengthening the public healthcare system, investing in healthcare recovery and prevention, and taking an integrated approach toward carbon neutrality—decarbonizing through building energy efficiency, renewable energy (solar, wind), electric vehicles and public transportation, energy demand management, and carbon-free mobility.

“Sustainable energy is good for our health,” said Nadeau.

“There’s a lot of reasons to be positive,” she said. “The youth movement is one—the most popular AP class in America is environmental science. Hooray! So build it, they will come. We're excited about this. But importantly, we need to make sure that all of us, all ages, contribute to being part of these solutions and the science.”

IDeA Symposium Video Recap

A short recap video of the 2024 RI All State IDeA Symposium held at The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.